April 2, 2017

By Lynda

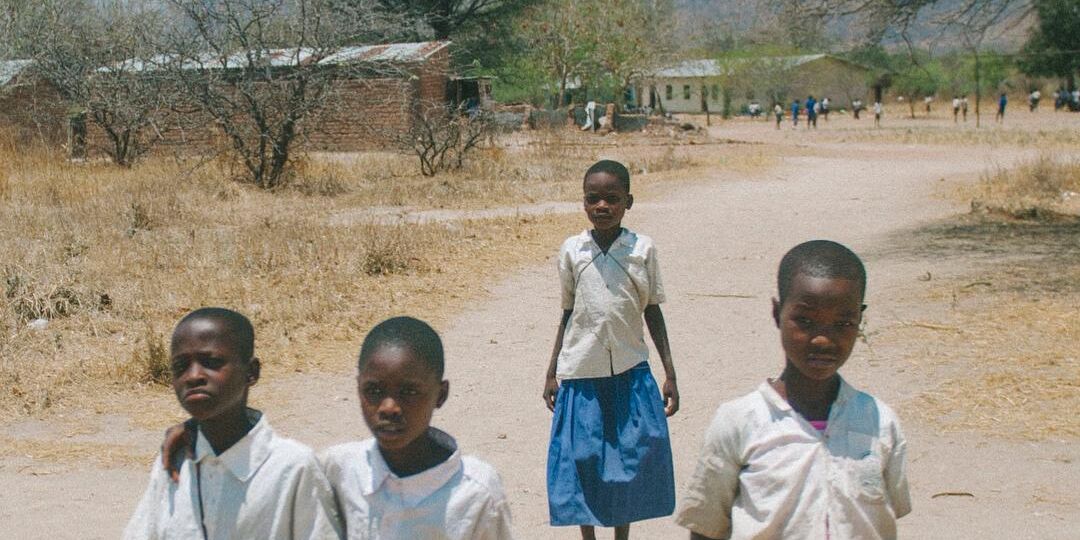

I look at the two little girls before me as I write this. Two beautiful little girls with their natural hair so perfectly parted into what I thank God for – loose braids. Every time they come over, I retrieve fond memories of growing up with my younger sister and notice many similarities. They have the same age difference as my sister and I, they love building forts with pillows and blankets, dancing to African music, and watching cartoons. My sister finds a kids channel for them and we both observe the images closely. The nuances of gender are everywhere and the girls frantically cry out saying they like the “pink one.”

Consequently, my sister and I start to talk about the kind of TV and stories our children will be exposed to. We both boldly predicted more diversity in kids shows, especially relating to gender, since we had earlier discussed Chimamanda’s Ngozi Adichie’s recent comments in a Channel 4 interview. Adichie said, “When people talk about, ‘Are trans women women?’ my feeling is trans women are trans women.”

Now, her comments started a necessary conversation about how we treat language and people’s gendered experiences. However, the purpose of this article is not about what she said, but rather looking at how she understands feminism and her invaluable new work “Dear Ijeawele, or A Feminist Manifesto in Fifteen Suggestions.”

“I matter. I matter equally. Not ‘if only.’ Not ‘as long as.’ I matter equally. Full stop.” To say this to a child, especially a girl, can be some of the most empowering words they carry with them throughout their lives.

When I first read Adichie’s original Facebook post in October 2016, the same powerful yet, gentle voice she captured me with in her 2013 TEDx talk, “We Should All Be Feminists” narrated this timely piece in my head. It was initially a letter to her friend on how to raise a feminist daughter. As I often sit these little girls, what part am I playing in raising them feminist? Would their parents approve? Coming from a patriarchal Kenyan cultural background but raising their daughters in the Diaspora with terminologies such as ‘cisgender’ for example, not existing in their English vocabulary nor mother tongue. I am confident that they trust my sister and I to look after their daughters, but would they trust our feminist input in raising their daughters with what Adichie outlines the premise as “I matter. I matter equally. Not ‘if only.’ Not ‘as long as.’ I matter equally. Full stop.” To say this to a child, especially a girl, can be some of the most empowering words they carry with them throughout their lives.

Indeed, to talk about feminism in relation to raising children and the heavy sprinkling of African culture – will inevitably strike a nerve. Firstly, starting with the often, misinterpreted definition of feminism – an individual who believes in the social, political and economic equality of the sexes. It is 2017, and I find that this basic definition is still not common knowledge and I appreciate that Adichie stands firm with it. It’s not to say that she does not see intersectionality or the historical and continuous problematic ways of white feminism, but she affirms we need a word to address an issue, and therefore she upholds feminist and feminism. I see well-intentioned parents, African and non-African, still raising their daughters differently to their sons. One example would be for their daughters not to fully partake in the same activities as boys or behave a certain way “because they are girls.” The words might not always be said but the actions are definitely implied. And it isn’t the fault of the parents either, because ways of being female and male are so deeply ingrained in them, that it becomes second nature to raise their child the way they were raised. But shouldn’t we be significantly more deliberate and conscious especially when bringing life into a changing world?

I am happier when the little girls come to me more excited about their Taekwondo practice than playing dress-up games on technology. When I did Taekwondo growing up I loved it, it taught me discipline and all I cared about is how strong my kiai was. I enjoyed learning how to do my make-up too, but I would often fall under more self-scrutiny because I was told, “all girls should know how to do this.” When these little girls get older and if they want me to do their eye shadow, I won’t refuse, but I won’t dare tell them what I was told.

For Adichie, feminism is always contextual. Therefore, the way she speaks and writes about feminism is mostly from what she knows and has experienced in the Nigerian context. The 15 suggestions she eloquently outlines in “Dear Ijeawele” will touch many young African women because she speaks from a context many of us can relate to. To raise or help raise a feminist child is not to shun African heritage or culture. But we must question our culture if it is teaching only girls how cook, while boys get to sit or play. Indeed, there’s a lot more complexity involved, but I often turn to cooking in these discussions because I deem it a necessary and ongoing example, since every human being needs to eat and know how to nourish one’s self.

Irrespective of genitilia.

If believing in the full equality of the sexes and how we raise the sexes is still not seen as something that needs work – that’s when one needs to read “Dear Ijeawele” as a reminder that we still have a long way to go.

To the little girls that may read this someday, I love you if you still like pink, I love you if you like green, and may you never say you had to do something you hated or didn’t do something you wanted “because you are a girl.”

Lynda

Writer

Images credits:

Raisa Mirza (www.raisamirza.com)