November 1, 2024

By Yedidya Ebosiri

Coffee-colored beauties, gravity-defying crowns: just how beautiful are our women! Mother Earth has blessed her daughters with unique features and a charm that transcends borders. Beauty in the plural, beauty with a thousand faces. Yet what makes them unique has long been the subject of violent dehumanization, and stereotypes are the remnants of this.

In the 15th century, colonization was firmly established on the African continent. To legitimize its existence, Europeans used racism to justify the exploitation of their African counterparts. In this way, their alleged moral superiority gave them the full right to dominate the continent’s peoples and turn them into a civilization. This unabashed racism spread outside the colonies, where stories fantasized by the colonists fueled beliefs about Africans in both North and South. At the heart of these incredible stories, the main characters are all the more mythologized when they are women.

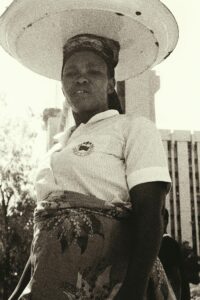

Southern Woman

Seductive and wild

An archetype of bestiality according to the discourses of yesteryear, African and black-skinned women have nothing human about them in the images conveyed by the colonists. They gave birth in public, they said, strutting around naked like primitive savages and carrying their children on their backs. In their writings, white thinkers and decision-makers insisted on the immense and fascinating appearance of African women, who were then subjected to the horrors of colonization. This paradox was underpinned by a pernicious fascination with the black woman’s body: its hypersexualization reached a climax in the 17th century, when it was endowed with an inordinate appetite and sexual prowess, rationalizing rape. The infamous Saartjie Baartman – Sawtche being her real name – also known by the pseudonym of the “Hottentot Venus”, was a symbol of this at the time of her ordeal.

While this extreme case of dehumanization is no longer socially acceptable, the stereotype of the African Jezebel, predatory and libertine, persists. This is why the black girl who suffers sexual assault “probably wanted it”; it’s also why the black best friend in TV series systematically plays the role of the temptress.

[…] the Sapphire, this caricature of the dominant, masculine, and violent slave woman, was the personification of the modern Black woman.

Bellicose and masculine

Fueled by Abrahamic religions associating dark skin with divine curse, the dark-skinned Black woman simultaneously embodies aggressiveness and cruelty. Masculinized due to the laborious tasks assigned to her by colonists, she endured multiple forms of aggression. Among the myths surrounding her, the Black woman was said to give birth without pain, allowing for an almost immediate return to work. In North America, these prejudices about women of African descent in post-slavery periods were perpetuated in the media; the Sapphire, this caricature of the dominant, masculine, and violent slave woman, was the personification of the modern Black woman.

Is this still the case today? Serena Williams might tell you yes. Naomie Musenga too. The cliché of the angry Black woman and that of the woman without pain are glaringly evident in both popular culture and hospital rooms; Mediterranean syndrome, the deadly belief that racialized people exaggerate their experience of pain, costs thousands of women’s lives. At the same time, the Sapphire stereotype coexists with that of the strong Black woman – the Strong Black Woman, which is thrown around carelessly on social media. An omnipresent belief, it’s an amalgamation of stereotypes about women of African descent: authoritarian, resilient, and nurturing. The needs of others come before her own. Although this cultural myth opposes that of the oppressed and hypersexualized Black woman, it proves to be a real iron ball on these women’s mental health.

Belly dancer and Scheherazade, the objectification of so-called “Oriental” women was particularly violent

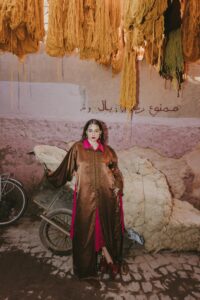

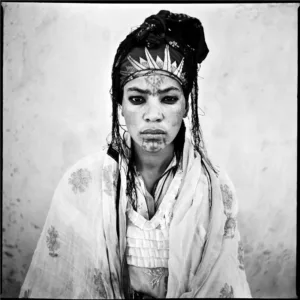

Northern woman

Sensual foreigner

While the colonization of sub-Saharan Africa and its derivatives are widely documented, the colonization of North Africa and its impacts on Maghrebi women are equally well-documented. Highly sexualized, the “Mauresque” — a name given to North African women derived from the term “Moor” — is a prejudice stemming from colonial pornography. Under the perverted gaze of European men, explicit photographs were mass-distributed across the continent during the era of French colonial domination in Algeria. The tales of One Thousand and One Nights then inspired erotic paintings of odalisques, slaves under the Ottoman Empire. Belly dancer and Scheherazade, the objectification of so-called “Oriental” women was particularly violent.

Silent servant

On the opposite end, there’s the added cliché of the veiled woman attributed to North African women; submissive, exotic, oppressed. In American films, they form only the backdrop, somewhat to signify that the main characters now find themselves in hostile territory. They speak very little. Their presence, almost imperceptible.

We will need to decolonize one mind at a time

Nowadays, these misogynistic and racist stereotypes remain deeply rooted in Western culture. Jasmine, lying on Aladdin’s flying carpet, is also the young Maghrebi girl from the suburbs represented for the umpteenth time in French cinema. In the same film, the veiled Muslim mother fades into the background, her voice taken away. There are numerous testimonies of Maghrebi women who have suffered discriminatory acts in the West, the bitter taste of which indicates stereotypical motives.

Woman of the world

A colonial legacy, negative stereotypes sometimes haunt the daily lives of women from the African diaspora in both the West and the East. Sometimes subtle, sometimes blatant. They are there, they exist. To deconstruct them will take time, kindness, and introspection. We will need to decolonize one mind at a time.

References

- Bedouret, D. (2011). Les stéréotypes de l’Afrique noire à travers le lexique et le discours de la géographie scolaire dans les manuels des années 1950 à nos jours. In M. Nglasso-Mwatha (éd.), L’imaginaire linguistique dans les discours littéraires politiques et médiatiques en Afrique (1‑). Presses Universitaires de Bordeaux. https://doi.org/10.4000/books.pub.35863

- CLANCY SMITH, J, Translated from American English by & ARMENGAUD, F (2006). Le regard colonial : Islam, genre et identités dans la fabrication de l’Algérie française, 1830-1962. Nouvelles Questions Féministes, 2006/1 Vol. 25. pp. 25-40. https://doi.org/10.3917/nqf.251.0025.

- Damla Altinkaynak (2021). L’exotique, la soumise et la terroriste : la représentation de la femme arabe à Hollywood. Sciences de l’Homme et Société. ⟨dumas-03405334⟩

- Godbolt, D., Opara, I., & Amutah-Onukagha, N. (2022). Strong Black Women: Linking Stereotypes, Stress, and Overeating Among a Sample of Black Female College Students. Journal of black studies, 53(6), 609–634. https://doi.org/10.1177/00219347221087453

- KATZENELLENBOGEN, Simon (1999). « Femmes et racisme dans les colonies européennes », Clio [En ligne], 9 | Posted online on May 22, 2006, accessed on September 9, 2024. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/clio/290 ; DOI : https://doi.org/10.4000/clio.290

- Lalaoui-Chiali, Fatima Zohra (2010). “Stéréotypes, écrits coloniaux et postcoloniaux : le cas de l’Algérie”, Itinéraires [Online] | Online since 01 May 2010, connection on 10 September 2024. URL: http://journals.openedition.org/itineraires/2125; DOI: https://doi.org/10.4000/itineraires.2125

- LE BIHAN, Y (2006). « La femme noire » dans l’imaginaire occidental masculin. L’Autre, 2006/1 Volume 7. pp. 43-59. https://doi.org/10.3917/lautr.019.0043.

Yedidya Ebosiri

Editor-in-Chief

As an eternal student, Yedidya is currently pursuing a graduate degree in public health after completing a bachelor's degree in kinesiology.

Her professional interests are rooted in the fight against social inequalities in health; she dreams of a healthier, fairer, greener world. In the meantime, she draws from her Congolese roots to advocate for a free and feminist Africa.

As a tutor for illiterate clients and a longtime mental health advocate, her intellectual curiosity and interpersonal skills characterize her emerging professional journey. Formerly an editor for a university newspaper, she continues to nurture her passion for journalism and looks forward to putting her writing skills at the service of her community. To her, Sayaspora embodies black excellence and social innovation, which is why she takes pride in contributing to the magazine's outreach.

Similar articles

January 20, 2025