July 12, 2020

By Abeer Almahdi

Before I learned the term “cultural appropriation,” I had no words to describe my feelings of discomfort when seeing the exploitation of my culture for profit. I did not understand my feelings of unease while browsing stores like Forever21 or Urban Outfitters, who commodify my culture for white consumers.

Earlier this month, I read an article by Montreal-based Moroccan blogger Mayasanaa about cultural appropriation. Mayasanaa’s article was the first time I read someone calling out the cultural appropriation of North African culture, and while her piece focused on Morocco, I believe her sentiments can be applied to the region as a whole.

Cultural appropriation is a colonial tool. The concept can be defined as, “the adoption or co-opting, usually without acknowledgment, of cultural identity markers associated with or originating in minority communities by people or communities with a relatively privileged status.” Appropriation aims to erase cultures through repossession. Often, to the point where the culture can become physically and financially inaccessible to the people it belongs to.

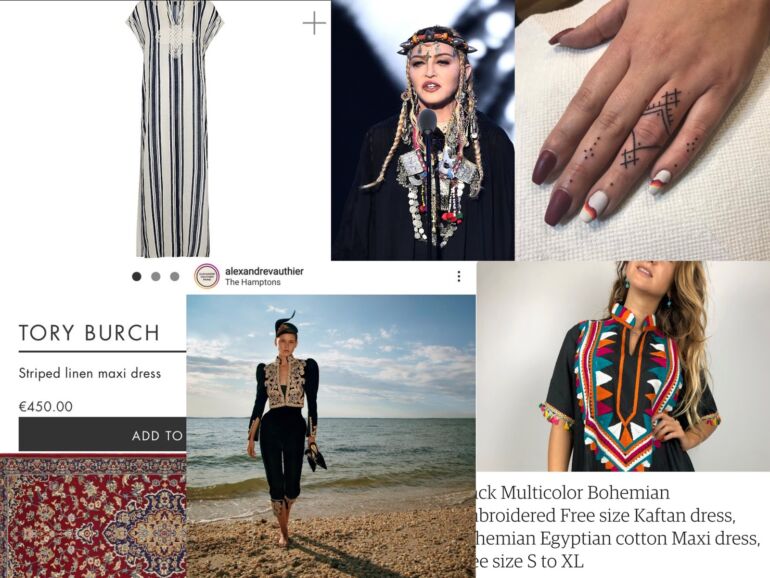

Cultural appropriation of North African cultures manifests in many different ways, often under the category of “boho” trends. I’ve seen brands sell Egyptian galabiyas, Algerian Karakous, kaftans, or tunics for hundreds of dollars. Furniture companies like IKEA will mass-make “oriental rugs.” I’ve seen white people with Amazigh or Arab traditional tattoos, without even knowing where these symbols come from. Or even white tattoo artists profiting off of our designs. Fancy French restaurants will sell overpriced Couscous and Tagines, claiming them as French cuisine. Celebrities like Madonna will literally wear North African culture as a costume.

Cultural appropriation is not just about material culture, but also about rituals, dances, and spiritual culture. Currently, most famous belly-dancers are white women. I remember at the start of quarantine, I attempted to get in touch with my culture and ancestors, so I tried to find online videos teaching belly-dancing. Belly-dancing (Raqs Sharqi) originated in Egypt as a feminine ritualistic dance by women, for women, and there are forms of belly-dancing across North African countries. In French, it’s called Danse du Ventre, often seen in Algerian cultures. I wanted to learn this dance from an African woman, but all I found online were white women orientalizing and commodifying my culture for views. Even in Egypt, white European women are taking dance jobs away from Egyptian women trying to protect the ancient art.

For hundreds of years, our countries have been colonized by France and Britain, where practicing our culture was persecuted and targeted by colonial authorities. Women would fight to dance and to perform rituals. Women with face tattoos would be fetishized and treated like animals by photographers. Now, our culture is not only persecuted and fetishized, but being actively stolen.

As Africans, we must decolonize our minds. We should reflect on our own decorations and fashions, and discover what cultures we even may be appropriating ourselves. We should call out appropriation when we see it, whether it’s by brands, tattoo artists, companies, bellydancers, or even our friends and family. This month of renaissance, I want to learn my dances, perform rituals, and reclaim my culture. I want to reclaim what my ancestors were forced to forget.

Abeer Almahdi

Writer

Abeer is an Egyptian-Syrian woman, born and raised in Kuwait. She currently lives in Montreal, where she attends McGill University. Abeer is also a poet, author and artist.

Images credits:

Featured image by @sundus.studios

Similar articles

September 18, 2021